Lt. Col. George Wilson

1729-1777

By Charles M. Wilson

Table of Contents

- Migration from Ulster to America

- Settlement and Marriage in Virginia

- French and Indian War - The Augusta Militia

- Residence in Romney

- Pennsylvania-Virginia Boundary Dispute

- Justice Wilson

- Death of Elizabeth

- Pennsylvania-Virginia Controversy Continues

- Lord Dumore's War and The Squabble Over Fort Pitt

- War for Independence from Britain

- Col. George's Relationship to James Wilson

- The Long Cold March of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment

- The Battle of Trenton and the Mystery of the Sword

- Col. Wilson’s Estate

- Who Was Col. George Wilson, the Man?

- A Man of Faith and Conviction

George Wilson is not what we would call a famous man by most historical standards. Although he did hold a number of responsible positions, was considered a leader and “gentleman” in the communities in which he lived and apparently achieved some degree of material prosperity, his influence on the events which shaped his day was not sufficient to gain mention in the scholarly works of American history. Fortunately, however, we can find some accounts of parts of his life in some published local and regional histories. Also, some of his letters survive and there are references to him in many public records so that it has been possible to compile what the writer hopes is a reasonably detailed and complete story of his life.

George Wilson is not what we would call a famous man by most historical standards. Although he did hold a number of responsible positions, was considered a leader and “gentleman” in the communities in which he lived and apparently achieved some degree of material prosperity, his influence on the events which shaped his day was not sufficient to gain mention in the scholarly works of American history. Fortunately, however, we can find some accounts of parts of his life in some published local and regional histories. Also, some of his letters survive and there are references to him in many public records so that it has been possible to compile what the writer hopes is a reasonably detailed and complete story of his life.

There is no public record that we have been able to locate which would definitely establish the date and place of his birth. The only record of any kind discovered thus far is an entry in the family bible of one of his grandsons. This states that he was born in 1729 in County Tyrone, Ireland, which is part of Ulster or, as we know it today, Northern Ireland.1Click to go directly to respective footnote. Use your browser's back button to return to the same spot.

18th Century IrelandHe was one of the people that were later to be known in America as the Scotch-Irish, the descendants of Lowland Scotch tenant farmers who were settled in Northern Ireland during the seventeenth century as part of a plan devised initially by King James I to introduce an element of Protestant English and Scotch to the Island to assist in his dealings with the predominantly Catholic natives.2 They and their descendants have been known variously as Irish Presbyterians, Ulster Irish, Ulster Scotch and, in this country, Scotch-Irish.3 The Scotch settlements in Northern Ireland were buffeted by a number of religious, political and economic upheavals during the seventeenth century but, nevertheless, managed to take hold and achieve some degree of prosperity by the dawn of the eighteenth. A new series of misfortunes in the form of economic hardships and persecution by the English because of their refusal to embrace Anglicanism was soon to befall them and many were prompted to emigrate to America. This migration started in 1717, although a few individuals and small groups had started earlier, and continued to a lesser or greater degree until the American Revolution.4

Migration from Ulster to America

Sometime between 1729 and 1750, George Wilson became a part of the migration from Ulster to America. There are no shipping lists or immigration records available, so we do not know whether he came with his family or, as a young man, alone. In fact, we have not been able to uncover any information whatsoever concerning his parentage. He did have a brother named Samuel, who settled in Virginia and was killed at the battle of Point Pleasant between the settlers and Indians in 1774.5 The first Ulster immigrants to America landed in New England where they thought they would be welcomed by the Puritans, whose Calvinistic faith did not differ in many essentials from their own Presbyterianism.6 Such was not to be the case, however, and most of the later settlers came where they would receive a warmer reception, which was often the colony of Pennsylvania, where all Christian faiths were tolerated more or less equally.7 The Scotch-Irish established a number of settlements in the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania,8and served as a buffer between the Indians and the settlers in the eastern portion of the colony. It was not long before the lack of availability of new lands and difficulties with their German and Quaker neighbors prompted some of the settlers, both old and new, to migrate southward to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, beginning in the 1730’s.9 It is there that we find the earliest mention of George Wilson in any public record.

Settlement and Marriage in Virginia

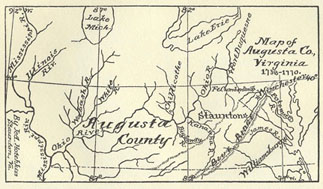

Augusta County 1738-1770Augusta County was established in 1738 by the Virginia House of Burgesses,10 and encompassed the Shenandoah Valley and all the western lands claimed by Virginia. “The foundation families of this settlement were so generally Scotch-Irish that the community came to be known as the ‘Irish Tract.’”11 George Wilson’s name appears in the Augusta County marriage records for February, 1750, but the bride’s name was not mentioned.12 We do know from other sources that she was Elizabeth, daughter of John and Agnes McCreery.13 He purchased 173 acres of land from Col. James Patton at the head of Broad Creek, in the fork of the James River on November 28, 1751,14 364 acres near the Potomac from James Trimble on March 15, 1757, and one lot in the town of Staunton from William Christian on November 17, 1757.15 He sold a 200 acre portion of the Trimble tract to Samuel Wilson (presumably his brother) on August 15, 1758.16 There may have been other purchases since he later bequeathed other property in Augusta County.

French and Indian War - The Augusta Militia

By the time George Wilson settled in Augusta County, English settlements had been established in North America for almost 150 years. During this time the European powers competed for dominance, and England found herself involved in disputes, or outright conflicts, with Spain, Holland, Sweden and, most importantly, France. The last and greatest colonial war between the two was, of course, what we know as the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) or, as it was called in America, the French and Indian War.17 The causes and events of this war are well recorded in history, and there is no need to dwell on them in any detail here. The Virginia frontier naturally bore the brunt of the fighting in that colony, and the records show that George Wilson did his share. His military career commenced on November 20, 1755, when he was qualified as a Captain of Horse of the Augusta Militia.18 During the course of the war, the county records  show he played an active part that included several encounters with his fellow Virginians, as well as the enemy. On July 15, 1756, he was “bound to good behaviour for having spoken disrespectfully of the Government,”19 and, on at least three occasions, disputes between George Wilson and other militiamen were taken to court.20 One of these cases, in June, 1757, is particularly interesting because of a comment made by the defendant, a certain Thomas Fimster, who had made charges that Captain Wilson had acted improperly while on duty by giving “provisions which belonged to the soldiers to women and children who had not right to it, and Captain Wilson’s character will in a little time be as well known here as it is in Pennsylvania.”21The verdict was in favor of Captain Wilson, but the most intriguing aspect of the matter is Fimster’s reference to Pennsylvania. We can reasonably assume that our subject may well have lived there, or at least passed through on his way to Virginia. Moreover, he might have had family there and returned for visits. Whatever the case, we must wonder what George Wilson had done in Pennsylvania that prompted Fimster’s charge. Was it before or after he settled in Augusta County? Could whatever it was have any bearing on his decision some years later to identify himself with Pennsylvania’s claims in its boundary dispute with Virginia? The answers to these questions are, in all probability, forever lost to us.

show he played an active part that included several encounters with his fellow Virginians, as well as the enemy. On July 15, 1756, he was “bound to good behaviour for having spoken disrespectfully of the Government,”19 and, on at least three occasions, disputes between George Wilson and other militiamen were taken to court.20 One of these cases, in June, 1757, is particularly interesting because of a comment made by the defendant, a certain Thomas Fimster, who had made charges that Captain Wilson had acted improperly while on duty by giving “provisions which belonged to the soldiers to women and children who had not right to it, and Captain Wilson’s character will in a little time be as well known here as it is in Pennsylvania.”21The verdict was in favor of Captain Wilson, but the most intriguing aspect of the matter is Fimster’s reference to Pennsylvania. We can reasonably assume that our subject may well have lived there, or at least passed through on his way to Virginia. Moreover, he might have had family there and returned for visits. Whatever the case, we must wonder what George Wilson had done in Pennsylvania that prompted Fimster’s charge. Was it before or after he settled in Augusta County? Could whatever it was have any bearing on his decision some years later to identify himself with Pennsylvania’s claims in its boundary dispute with Virginia? The answers to these questions are, in all probability, forever lost to us.

On November 19, 1761,22 another case appears in the Augusta records wherein George Wilson was sued by Thomas Gilmore in a dispute over some plunder recovered from the Indians, who raided a plantation where he lived, killed his parents and carried off everything. The militia pursued them and recovered most of the plunder, including a horse which was the object in question. As far as we can tell from the record, the inhabitants of other plantations in the area which were also raided promised that those pursuing the Indians could keep any property they recovered if they could free the prisoners who had been taken. Gilmore apparently was not a party to the agreement, and sought the return of his horse. We do not know how the case was settled.

“You are a public liar and you impose upon the public; you endeavor to raise and support yourself at the expense of others and the prejedice [sic] of the public.”

The last case of record involving a militia dispute is the most interesting and revealing. It seems that a general muster was called in October of 1761, at which the Colonel of the County, William Preston, ordered Captain Wilson to read a paper justifying his drafting the militia for service on the frontier. Also present was one Israel Christian, a member of the House of Burgesses, who had allegedly been critical of Preston’s action. We can assume that Captain Wilson enthusiastically supported his Colonel, since, after reading the aforementioned paper, he turned to Christian and said, “You are a public liar and you impose upon the public; you endeavor to raise and support yourself at the expense of others and the prejedice [sic] of the public.”23 Unfortunately, as in the Gilmore case, there is no record of the ultimate verdict.

“Whether or not it was due to his dispute with Israel Christian, the records show that George Wilson had moved from Augusta County in the same month and year that the suit was filed, February, 1763.24 His new home was to be in Romney, Hampshire County, which is now part of West Virginia. The Augusta records show that he traveled the 80 miles between Romney and Staunton to appear as a witness on two occasions in the spring and summer of 1765.25 By 1763 the French and Indian War was drawing to a close, but there was still trouble with the Indians in Hampshire County, and Wilson was as actively involved in the militia there as he had been in Augusta county, as the following passage from the proceedings of the House of Burgesses for November 9, 1764, makes clear:

“Mr. George Washington laid before the House a report from the Commissioners appointed by Act of Assembly to examine, state and settle, the account of the Pay, Provisions, Arms and Necessaries, for the Militia of the Colony; which was read and is as follows: ...It also appeared that George Wilson had obtained a Commission to act as Major of the County of Hampshire, and that he had the command of a Company of the Hampshire Militia given him by Col. Stephen; that the said Wilson has also been brave and active in the Command of the said Company. . .

“That Captain Luke Collins of the Hampshire Militia, was ordered by Col. Stephen to join Major Wilson with as many able men as should be in his power to collect in a short time, and to march in quest of a party of Indians who had killed several of the Inhabitants of Hampshire, at a place called Welton’s Meadow . . . That he, with Major Wilson and his party, did overtake the Party of Indians at Cheat River, attacked and killed three of them, wounding several others, and retook a prisoner who had been carried from Welton’s Meadow, together with a large Quantity of Plunder.”26

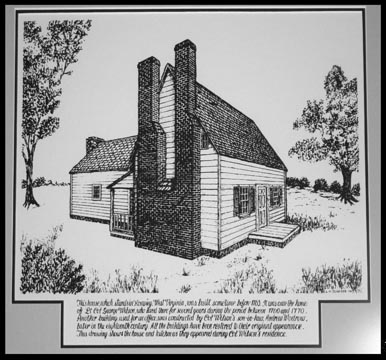

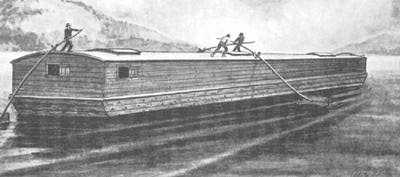

Pen and Ink by L. H. Dumser © 1974

Residence in Romney

photo by C. Wilson ©1974The records of the Hampshire Court have not yet been compiled and published as have those of Augusta, so we cannot document many of George Wilson’s deeds there, or his length of residence. One reminder of his stay there does exist, however, and it is the most remarkable of any mementos we can find of his life in any of the three locations where he settled. His home in RomneyClick to open page with photos of the interior of the house. This is a separate web site for what is today known as the Mytinger House. still stands and has been restored to its original state.27 He retained ownership after he left Romney, and it was mentioned in his will, wherein he left it to his daughter Elizabeth.28 A drawing of the home as it probably appeared during his residence is included in this sketch [ed. note: Above]. The present day visitor to Romney will find that it has been restored beautifully, together with another building on the property which was added by Col. Wilson’s son-in-law, Andrew Wodrow, later in the eighteenth century.29 The house was not built by Col. Wilson but was purchased by him from Hugh Murphy.30 Current research has not yet revealed who built the house and when. It is known that it is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, dwellings still standing in West Virginia.31

photo by C. Wilson ©1974

George Wilson’s residence in Romney was not very long, but we cannot determine its exact length since we don’t know precisely when he moved there or when he left. He It is safe to say he departed Augusta County between October, 1761 and February, 1763, since the former date was his encounter with Israel Christian at the militia muster and the latter is taken from an entry in the Augusta Court records showing him as having moved.32 The 1763 entry was probably made after the fact, so we can conclude that he probably moved during 1762.

Col. George's home in Romney, WV His departure from Romney is equally difficult to determine as two different sources give the date as 176533 or 1768.34 He was appointed a Justice for Bedford County, Pennsylvania, when it was formed in 1771 and it does not seem very reasonable that someone just arrived from another colony would be so honored; so we can assume that either of the dates could be correct.35 His property in what is now Springhill Township, Fayette County, was patented in 1770, which was probably the earliest possible interval after the Pennsylvania Land Office was opened in 1769.36 While this is interesting, it doesn’t help us much in establishing with any accuracy the date on which he actually took up residence. The 1763 date seems too early as it is difficult to imagine that someone would move from Augusta to Hampshire and then remain there for only a year or less. Also, the records of Augusta County show that “George Wilson, gent.” traveled eighty miles from Hampshire to appear as a witness on March 23 and August 24, 1765.37 It could be possible, though, that he went to the Monongahela as early as 1763 to stake his claim and waited for several years before actually moving there with his family. Whatever the case, we simply will have to leave that date of his move as an open question and assume that he had no reason for leaving Romney other than to take advantage of the promise of a new land.

Pennsylvania-Virginia Boundary Dispute

Virginia’s Charter of 1609 could be interpreted as giving jurisdiction to that colony of a vast part of North America that includes all of the United States from the Ohio Valley northwest to the Pacific Ocean.38 Their royal charters determined the boundaries of all the colonies and the lack of knowledge of North American geography resulted in some ambiguities that were to be the cause in later years of some heated inter-colonial boundary disputes.39 One such dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania was settled by a line run in 1767 by two English surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon.40 Because of Indian opposition the line was not run its full length until after the American Revolution, thus leaving the western limits of Pennsylvania open to question and precipitating a bitter and violent confrontation between settlers of that colony and Virginia as they moved into the lands adjacent to the Monongahela Valley.41

After the close of the French and Indian War in 1763, Virginia settlers began filtering through the Appalachian Mountains to the lands emptied by the Ohio River and its tributaries.42 A few traders had made homes there some years earlier but there was no real migration until after the danger from the French and their Indian allies had been reduced. The Pennsylvanians did not start arriving in strength until after the Indian titles were extinguished by the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768.43 Shortly thereafter, in 1769, Pennsylvania opened a land office so that her settlers could officially obtain titles.44

With partisans of both colonies now in the area and the rival colonial governments attempting to establish their authority, what naturally followed was “a series of arrests and counter arrests, long continued, resulting in riots and broils of intense passion. Every one who, under the color of an office held under the laws of Pennsylvania attempting any official act, was likely to be arrested and jailed by persons claiming to hold office under the government of Virginia. Likewise, were Virginia officials liable to arrest and imprisonment by the Pennsylvania partisans.”45

Justice Wilson

It would be natural to assume that George Wilson, having come from Virginia, would take her cause as his own, but we know that the opposite is true. As to his reasons, however, we can only guess. He may have given his allegiance to Pennsylvania because of economic interest, personal loyalties to friends or family in that colony — it is here that Fimster’s accusation comes to mind — or he may have looked at the situation and simply become convinced that Virginia’s claims were not valid and therefore insupportable. Whatever his reasons, the Virginians did not exactly form a stampede in their rush to congratulate him and wish him well in his new office when he was appointed a Bedford County Justice in 1771. Previously, Cumberland County had jurisdiction for Pennsylvania but the new county was formed to accommodate the needs of the growing population.46 Justice Wilson was no man to allow opposition to dissuade him from what he perceived to be his duty, as the following letter to Arthur St. Clair makes clear:47

My Dear Capt.: I am sorey that the first Letter I ever undertook to Write you should Contain a Detail of a Grievance so Disagreeable to me; Wars of any Cind are not agreable to aney Person Possessed of ye proper feelings of Humanity, But more Especially intestin Broyls. I no soomer Returned Home from Court than I Found papers containing the Resolves, as they called them, of ye inhabitants to ye Westward of ye Laurall hills, were handing fast abowt amongst ye people, in which amongst ye rest Was one that they Were Resolved to appose Everey of Pens Laws as they Called them, Except Felonious actions, at ye Risque of Life, & under th penelty of fiftey pounds, to be Recovoured or Leveyed By themselves off ye Estates of ye failure. The first of them I found Hardey anugh to offer it in publick, I Emeditly ordered into Custotey, on which a large number Ware assembled as Was Seposed to Resque The Prisonar. I endavoured, By all ye Reason I was Capable of, to Convince them of the ill Consequences that would of Consequence attend such a Rebellion, & Hapely Gained on the people to Consent to Relinquish their Resolves & to Burn the Peper they had Signed — When their forman saw that the Arms of His Centrie, that as hee said Hee had thrown himself into would not Resque him By Force, hee catched up his Rifle, Which Was Well Loded, Jumped out of Dors, & swore if aney man Cam nigh him hee Would put What Was in his throo them: the Person that Has him in Custody Called for assistance in ye Kings name, & in pirtickelaur Commanded my self, I told him I Was a Subject & Was not fit to Comand if not Willing to obay, on which I watched his Eye until I Saw a Chance, Sprang in on him & Sezed the Rifle by ye Muzle and held him, So as he Could not Shoot mee, untill more help Got in to my asistance, on which I Disarmed him & Broke his Rifle to peeses. I Resd a Sore Bruze on one of my arms By a punch of ye Gun in ye Struggle—Then put him under a Strong Guard, Told them the Laws of their Contrie was stronger then the Hardiest Ruffin amongst them. I found it necessery on their Complyance & altering their Resolves, & his promising to Give him self no more trouble in the affair, as hee found that the people Ware not as hardey as hee Expected them to be, to Relece him on his Promise of Good Behavour. I am afraid Sum Who Have Been two much Countenanced By their King & ye province of Pensallvania are Great Accesoreys to these factions, & God Knows where they May Eind. I have, in my Little time in Life, taken the oath of Allegence to His Majestie seven times, & allways Did it with ye Consent of my whole Heart, & am Determined in my proper place to Seport the Contents therof to ye outmost of my power, as I look on it as my Duty to Let those things be known to Government, & my acquaintance at Philladelphia is none. I Expect you will Comminicat those things to them, that the Wisdom of Government may provide Remedies in time, as there are numbers in the Lowr parts of ower Settlement still incressing ye faction. It Givs mee Grate Pleasure that my nighbours are Determined not to Joyn in the faction, & I Hope the Difrant Majestrits in this side ye Mountains will use their influence to Disorage it. I understand Grate thrates are made against mee in partikolaur if possible to intimidate mee With fear, & allso against the Sherifs & Constables, & all Ministers of Justice, But I Hope the Laws, ye Bullowrks of ower nation, will be Seported in Spight of those Low Lifed trifling Raskells.

Give my Complements to Mr. George Wood, Mr. Dohertey & Mr. Frazor, and Except of myn to your Self, Who am, with Respect Your most obt Hble Sert.

G. WILSON Springhill Township, Augt 14th, 1771 To Arthor St. Clair, Esqr.

Arthur St. ClairThe recipient of the letter, Arthur St. Clair, was born in Scotland and served as an officer in the British army. After the French and Indian War he resigned his commission and settled in America. At the time Bedford County was formed, the governor appointed him a Justice and, simultaneously, to several other offices. Later, when the American Revolution broke out, he joined the Continental Army and served with distinction. President Washington appointed him first governor of the old Northwest Territory.48

Death of Elizabeth

In addition to his difficulties with the Virginians, Col. Wilson also had to bear the loss of his wife at about this time. There is no record of her death or burial but the records do show that he was widowed.49

The approximate date of her death can be reckoned by assuming that it would, by biological necessity, take at least seventeen or eighteen years to bear eleven children following in 1750.50 This means that she was probably living as late as 1767 or 1768. In May of 1772, George Wilson filed suit against the executors of John McCreery’s will and, in that court entry, Elizabeth is  referred to in the past tense so it is not unreasonable to fix the period between 1768 and 1772 as the most likely time of her death.51 Life on the frontier was not conducive to raising a family without a mother and men who were widowers did their best not to remain so for long. Our subject was no exception and married Sabina Stuart52 of Augusta County by whom he had a son, Samuel Stuart Wilson, who did not, to the best of our knowledge, survive childhood.53 Following the death of Colonel Wilson, Sabina married Samuel Williams.54

referred to in the past tense so it is not unreasonable to fix the period between 1768 and 1772 as the most likely time of her death.51 Life on the frontier was not conducive to raising a family without a mother and men who were widowers did their best not to remain so for long. Our subject was no exception and married Sabina Stuart52 of Augusta County by whom he had a son, Samuel Stuart Wilson, who did not, to the best of our knowledge, survive childhood.53 Following the death of Colonel Wilson, Sabina married Samuel Williams.54

Pennsylvania-Virginia Controversy Continues

The boundary dispute continued to wage hot and heavy but Colonel Wilson did not let his involvement destroy his friendship for his Virginia comrades as can be seen by his letter to Major Luke Collins, who served with him in the Hampshire Militia and accompanied him on the expedition to the Cheat River some eight or nine years earlier.55

Dr Sir,

I recd yours of the 5th instant, and am sorry of ye Disppointment of your Company. We had the happines of Joyning in Sentement in ye Colony of Virginia, and as I may say, even Waiding throo blood, in Supporting ye caus of our Countrie, hart in hand. But it looks as if we must Difer in ower way of thinking here. I allways look on it as ye Duty of Christions and good Subjects to obey, and the Privilege and right of ye Legislative powers to Dictate, & therefore, untill I am oppressed by Burdensome and unjust laws, I shall still chuse ye former. I am doubtful you mistook ye intension on foot, and inste’d of Meeting, to Prevent as you say, ye tumults of ye People, augment ought to a been put in you. I presume are Better acquaint with my Sentements in Regard of friendship, than to think if we must difer in Sentement, that it will raze ye foundation of my former Good wishes to you and your family. So I hope you will Pardon me for difering with you—not with you, but ye Poisonous Faction, in regards to Grants from the Colony of Virginia. I well know that the Honourable Counsell of that Colony last year sat on ye affairs relative to ye Grants and Land on ye Western Waters, which they had Claimed and Surveyed before ye late purchase, and the Result of the Counsel was, that they had no right to ye Lands before purchased of ye Indians, and of consequence ye Grants were of none Efect, at which time strict orders were given to ye Serveyors not to stratch a Chain on them Lands, and as for other Grants from ye Crown to Gentlemen, ye whole world must well believe it must be ungranted Lands that are given to them, and not ye Property of other Propietors; you, yourselves, justly observe the Boundries are not set settled, so it is unknown to you how far Pensalvania extends.

I dar not impeach ye Propriatories of Pensalvania with such glaring acts of unjustice, as your Superscription paper sets forth. I think it is too daring, and a matter too high for me; besides, I don’t understand where ye Sute is to be commenced. Nay, I can see no face it can bair, that can posably take with any unprejudiced, disinteristed set of Mankind, that have half of one eye open, unless it be to encress faction and feed a set of Hungry Lawyers. I plainly see that ambition will make men Drunke as well as Liquer. I am surprised to see such inconsistancies from Men of tolerable sence, but much more from where it coms.

I am still your harty wellwisher, and humble Servant,

G. WILSON July ye 9th, 1772 To Major Luke Collins

This letter gives us some insights into the writer’s personality and beliefs. Apparently, Major Collins was in his neighborhood and was unwilling or unable to see his old militia comrade. “Ye late purchase” undoubtedly refers to the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, which we know was the instrument by which Indian title to lands south of the Ohio was extinguished. Colonel Wilson’s basic points were that (1) the Colony of Virginia, by its own admission, had no authority to grant any lands in the region before 1768, (2) could only grant lands within its undisputed jurisdiction and (3) the western boundary of Pennsylvania was conceded by all parties to be still undetermined. Furthermore, he obviously felt that some of the Virginians were motivated as much by ambition as by ties of loyalty. In all fairness, however, we cannot guarantee that the motives of the Pennsylvanians’ were of the highest, our subject included. One thing we can definitely say about his position is that it was far closer to the ultimate solution than was that of his Virginia opponents.56

The year 1773 saw the boundary dispute continue to intensify as it rumbled across the hills and valleys of southwestern Pennsylvania (or northwest Virginia depending on the perspective of the reader).

John Penn (1725-1795)Pennsylvania reacted to the increased Virginia activity by creating a new county, Westmoreland, from a portion of Bedford on February 26, 1773.57 George Wilson was one of the Justices of the new county58 and was also appointed one of the trustees to determine the location of the county seat.59 He did not hesitate to disagree with his Pennsylvania associates when the occasion arose, and refused to join with the other three in their decision to establish Hannastown as the temporary county seat, a matter of some controversy, as many residents of the new county felt that Pittsburgh would be a more suitable location. his position was expressed in the following letter to Governor Penn written on October 8, 1773:60

Honoured Sir,

After congratulateing you on your Safe Arrivall to ye State of your Govourment, I Beg Leave to acquaint you that Since ye Constetution of ye New Countey of Westmoreland, We Who Ware appointed Trustees Have Met twice in order to consult on Sum things Relative to ower Dutey in that trust. I apprehended that it Was ye Sence of His Honour ye Govournour and ye Assembley at ye time, that ye Courts Ware appointed to Hold at ye Hows of Mr. Robart Hannow, that they Should Hold there untill the present unsettled State of ye Westrin Boundrey might be more perfectly asertained, for Which Reason I could not Joyn With ye other trustees in Making a Report to your Honour, Which Report I presume is com to Hand Before now. It Was My Advice, that a Letter first should be sent to your Honour to Know your Sence of ye matter Whether it would be advisable, (as there is a Goale and a Sort of a Courthows in Which ye Counties Busness may be Don in,) to pospon the Fixing aney perticular place for a Countey Seat for Sum time Longer untill at Least, We had your advice in ye matter. But As They Rather chose to Make a Report, I Did not thinke proper to Joyn in that. I Gladly Would Do My Dutey for ye Rest & Would be Sorey to Mistake it. I Would be Extremely Glad to Know your Sence of ye Matter & am Sorrey to acquaint you of ye unhapey diferances occasioned by Sum ill minded persons, As they Say By Reason of ye unsettled State of ye Westerin Bounderie.

I am with profound Respect, Your Most ob’t H’ble Serv’t,

G. WILSON Westmoreland, Oct’r 8th, 1773.

Lord Dumore's War and The Squabble Over Fort Pitt

While the Pennsylvanians were involved in this minor dispute, something less than perfect harmony was prevailing among the Virginians. Dr. John Connolly was appointed by the Virginia Governor, Lord Dunmore, as military commissioner and commandant at Pittsburgh. The situation deteriorated further as 1774 began. On January 6 Connolly posted public notices in Pittsburgh ordering the population to assemble as a militia on January 25 for the purpose of strengthening Virginia’s authority there.61 In order to prevent this assembly, St. Clair ordered that Connolly be arrested before it could take place and later released him on his promise that he would appear before the Westmoreland Court when it convened in April.62 He did appear as promised, accompanied by some two hundred armed militia, exchanged views on the situation with the Pennsylvania magistrates and departed.63 The President of the Westmoreland Court, William Crawford, wrote an account of the incident to Governor Penn and, at the close of his letter said: “For further particulars concerning the situation of the country, I refer you to Colonel Wilson, who is kind enough to go on the present occasion to Philadelphia.”64

Battle of Pt. PleasantPresumably, Colonel Wilson returned from Philadelphia in May or June of 1774. If it were not for the troubles with the Indians that were soon to develop, the boundary dispute might have erupted into open warfare between the two colonies at that time.65 The Shawanese and Mingoe Tribes were worried about the incursions of the “Long Knives” as they called the Virginians, and what is knows as Lord Dunmore’s War, the last colonial Indian war, exploded on the frontier in the fall of 1774. The climactic episode was the battle of Point Pleasant, fought at the junction of the Kenawah and Ohio Rivers in October.66 One of the fatalities was Samuel Wilson, brother of George.67

Augusta County was becoming increasingly difficult to administer because of its vast size so Lord Dunmore created the District of West Augusta, a semi-autonomous entity which existed until 1776, when the Virginia Assembly split it into three new counties.68 The war between Virginia and the Indians was concluded at about the same time, so Connolly and his followers were able to turn their undivided attentions to the Pennsylvanians. During the first half of 1775 the time was “largely taken up in the Western Country with stirring events, caused by the conflict of jurisdiction between Pennsylvania and Virginia concerning so much has already been given.”69

Valentine Crawford, writing to George Washington on June 24, 1775, brings Colonel Wilson’s name once again into the controversy. “The Pennsylvanians came to Ft. Pitt with the sheriff and about twenty men, and took Major Connolly about midnight and carried him as far as Ligonier... On Major Connolly being taken, the people of Chartier’s came in a company and seized three of the Pennsylvania magistrates who were concerned in taking off Connolly—George Wilson, Joseph Spear and Devereux Smith. They were sent in an old leaky boat to Fort Fincastle (Wheeling) under guard.”70 A few weeks later, Arthur St. Clair wrote to Joseph Shippen: “In my last I gave you an account of the taking of Mr. Connolly, and mentioned some of the consequences I apprehended from it. They have since been disagreeable enough to Mr. Smith, Mr. Speare and Colonel Wilson, who were immediately made prisoners by way of reprisal, and sent off in a flat to Wheeling, where they were detained till the news of Connolly’s return, and in the mean time were exposed to every species of insult and abuse.”71 Colonel Wilson was ordered to appear before the West Augusta court to answer for his part in the affair but we probably can assume he ignored the summons. Besides, at this point, events were taking place elsewhere that would cause the partisans of both sides to set aside their differences in the boundary dispute and direct their attentions toward other matters. The Connolly abduction, and its aftermath, brings to a close the record of George Wilson’s involvement in the Pennsylvania-Virginia controversy.

War for Independence from Britain

News of the battles of Lexington and Concord reached Westmoreland County during the first half of May, 1775. The residents met at Hannastown on May 16 and unanimously adopted a set of resolutions that—while reaffirming their allegiance to the Crown—stated their determination to resist by armed force if necessary the encroachment upon American liberties by “wicked ministry and corrupted Parliament.”72 The Virginians met at Pittsburgh and passed a similar set of resolutions.73 As the situation deteriorated further, each colony took measures for its own defense and the Continental Congress assumed control of the army encamped around Boston. The state of Pennsylvania raised several regiments for Continental service and submitted the names of field officers for one of them, the Eighth, to Congress for approval. They were confirmed on July 20, 1776, and their names were: Aneas McKay, Colonel; George Wilson, Lieutenant Colonel; and Richard Butler, Major.74

The Eighth Pennsylvania was originally raised for the defense of the frontier, but the misfortunes that befell Washington’s army in New York and New Jersey during the summer and fall of 1776 caused a crisis that required a change in plans. All available forces were ordered under his command and the troops raised by Pennsylvania and New Jersey were ordered to “fall in on the communication leading from New York to Philadelphia, at Brunswick, or between that and Princeton.”75 This meant that Colonel Wilson’s regiment would have to undertake a march of some four hundred miles from its encampment at Kittanning, and he expressed his feelings about the situation in a letter to James Wilson, a Member of Congress and Signer of the Declaration of Independence.76

KETANIAN, Decr 5th, 1776

“Dr Colonall: Last evening We Recd Marching orders, Which I must say is not Disagreeable to me under ye Sircumstances of ye times, for when I entr’d into ye Service I judged that if a necesety appeared to call us Below, it would be Don, therefore it Don’t come on my By Surprise; But as Both ye Officers and Men understood they Ware Raised for ye Defence of ye Western Frontiers, and their fameleys and substance to be Left in so Defenceless a situation in their abstence, seems to Give Sensable trouble, altho I Hope We Will Get over it, By leving sum of ower trifeling Officers Behind who Pirtend to Have More Witt than seven men can Rendar a Reason. We are ill Provided for a March at this season, But there is nothing Hard under sum Sircumstances. We Hope Provision Will be made for us Below, Blankets, Campe Kittles, tents, arms, Regementals, &c., that we may not Cut a Dispisable Figure, But may be Enabled to answer ye expectation of ower Countre.

I Have Warmley Recommended to ye officers to Lay aside all Personall Resentments at this time, for that it Would be construed By ye Worald that they made use of that Sircumstance to Hide themselves under from ye cause of their countrie, and I hope it Will have a Good Efect at this time. We have ishued ye Necesery orders and appointed ye owt Parties to Randevous at Hanows Town ye 15th instant, and to March Emeditly from there. We have Recemended it to ye Militia to Station One Hundred Men at this post untill further orders.

I Hope to have ye Pleasure of Seeing you Soon, as we mean to take Philodelphia in ower Rout. In ye mean time, I am, With Esteem, your Harty Wellwisher and Hble Sert,

G. WILSON To Col. JAMES WILSON, of the Honorable the Cont. Congress, Phila.

Col. George's Relationship to James Wilson, Signer of the Declaration of Independence

There have been references in the lineage of some of George Wilson’s descendants stating that he was the brother of James. An examination of the facts has shown, however, that there is no possibility of such a relationship.77 In the first place, they were born thirteen years apart in different places and James was the eldest son of William and Alison Lansdale Wilson. He had three older sisters and three younger brothers named John, Andrew and William.78

James and George probably became acquainted when the former was appointed an Indian Commissioner for the Continental Congress and came to Pittsburgh in August of 1775, to negotiate a treaty with the Indians that would insure their alliance or at least their neutrality in the struggle with Britain.79 The Secretary for the Commissioners during their two months’ stay in Pittsburgh was Arthur St. Clair, and it seems quite likely that he would have taken the opportunity to introduce the distinguished visitor to the local gentry including, of course, George Wilson.

In conclusion, this writer can say that no evidence whatsoever could be found to substantiate any kind of family relationship between George and James Wilson, other than their sharing a very common surname. All the facts that have been gathered seem to show conclusively that they certainly were not brothers.

The Long Cold March of the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment

The march of the Eighth Pennsylvania through the wilderness of Pennsylvania must have been hard even by eighteenth century standards. We are all familiar with the historical accounts of the bitter cold experienced by Washington’s army as it crossed the ice clogged Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776, and the conditions in the mountains several hundred miles to the west hardly could have been any better. One of the participants will be quoted later who briefly described the conditions they faced on their way to “answer ye expectation of ower Countre.”

There were also some difficulties experienced on the way which were not related to the weather. Col. Wilson had hinted that all was not complete harmony among the officers of the regiment before it marched from Hannastown. It seems that officers were appointed upon the recommendation of committees and the system logically led, in some cases, to the junior officers attempting to dictate the choice of field officers. The Eighth Pennsylvania was so plagued by such dissention that it became the subject of a letter from General William Thompson to Arthur St. Clair dated January 11, 1777, and another from James Wilson to St. Clair written three days later.80 The regiment probably passed through Carlisle in early January as both letters were written from that town and it is a safe assumption that some of the aggrieved officers sought friendly influence on their behalf. There is no mention of any part Lt. Col. Wilson played in the affair but, from what we know of his contentious nature, it was undoubtedly active if his health permitted.

There were also some difficulties experienced on the way which were not related to the weather. Col. Wilson had hinted that all was not complete harmony among the officers of the regiment before it marched from Hannastown. It seems that officers were appointed upon the recommendation of committees and the system logically led, in some cases, to the junior officers attempting to dictate the choice of field officers. The Eighth Pennsylvania was so plagued by such dissention that it became the subject of a letter from General William Thompson to Arthur St. Clair dated January 11, 1777, and another from James Wilson to St. Clair written three days later.80 The regiment probably passed through Carlisle in early January as both letters were written from that town and it is a safe assumption that some of the aggrieved officers sought friendly influence on their behalf. There is no mention of any part Lt. Col. Wilson played in the affair but, from what we know of his contentious nature, it was undoubtedly active if his health permitted.

There is no record of exactly when the regiment arrived in New Jersey, but in his reply to James Wilson’s letter, General St. Clair wrote from Morristown on February 10 that “Colonel Mackay is not yet come up, and I have just heard that he lies sick at Trenton, but I have made the General (Washington) acquainted with the confusion and the cause of it that prevails in that regiment and I have no doubt that the authors will meet with their deserts.”81

The Battle of Trenton and the Mystery of the Sword

Some sources, in many cases the same ones that identify George Wilson as the brother of James Wilson, state that he was present at the battle of Trenton. A search of the accounts of the battles of Trenton and Princeton fails to find any mention of Lt. Col. George Wilson or the Eighth Pennsylvania Regiment.82 This is reasonable since the unit hardly could have been at Trenton on December 26, 1776, if it did not pass through Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until January 11, 1777. Even if Col. Wilson was detached from his unit and went on ahead by himself or with a small advance party, covering the four hundred and fifty odd miles between Hannastown and Trenton in nine days during early winter would have been a feat of heroic proportions. Had he done so General St. Clair, who was present, certainly would have mentioned his presence when writing to James Wilson about the discord and turmoil in the regiment.83

18th Century Sword The only physical evidence of his participation in the famous battle with the Hessians was a sword that was in the hands of a widow of one of his descendants, a Mrs. Charles B. Wilson, who was living in Ashland, Kentucky, in 1958. Its handle was inscribed thusly: “Sword of Col. George Wilson, Trenton, Christmas, 1776.” The scabbard bore the inscription “G. Wilson, 1777.” The only plausible explanations seem to be that (1) the government might have authorized the issuance of commemorative swords at some later time to all officers of units that were in the vicinity of Trenton and thus considered part of the campaign or (2) that someone may have had Colonel Wilson’s sword inscribed sometime after his death in the mistaken belief that he actually was there. Unfortunately, Mr. And Mrs. Charles B. Wilson did not have children and the whereabouts of the sword are now a mystery.84

Riddled with casualties from its long march and torn by discord among its officers, the regiment was in a pitiful state when we next find mention of it bivouacked in Quibbletown (now known as New Market), New Jersey, on February 28, 1777. A regiment of militia from Essex, Massachusetts, was in the same area and its commander, Timothy Pickering, recorded in his journal of March 1:85

“Dr. Putnam, in the forenoon brought me a billet, of which the following is a copy:

“‘ Dear Sir,

As our battalion is so unfortunate not to have a doctor, and, in my opinion, dying for want of medicine, I beg that you will come down to-morrow morning, and visit the sick of my company. For that favor you shall have sufficient satisfaction from your humble servant,

James Pigot

Captain of the Eighth Battalion of Pennsylvania

Quibbletown, February 28th, 1777.’”“I desired the Doctor by all means to visit them, and administer such medicine as was needed...They were raised about the Ohio, and had traveled near five hundred miles, as one of the soldiers (who came for the Doctor) informed me; for about one hundred and sixty miles over the mountains, never entering a house, but at night building fires and encamping on the snow. Considerable numbers, unused to such hardships have since died. The Colonel and Lieutenant-Colonel are among the dead. “The Doctor returned and told me he found the battalion in cold, shattered houses, and very nasty, to which causes he partly imputed their diseases. Both these causes it was greatly in their power to remove, the latter entirely; but they had been careless. They importuned the Doctor to visit them again to-morrow.”

Col. Wilson’s family became aware of his death when his Negro slave, who had accompanied him, returned home leading his master’s riderless horse.86 There is no record of the exact date of his death or of its cause. The date reasonably can be placed between February 10, the date of General St. Clair’s letter to James Wilson, and February 28. The cause was not due to enemy action since his heirs applied for a pension some years later and it was rejected on the grounds that only those who were killed as a direct result of hostile action were eligible.87 We can only guess that the cause of death was continued exposure to the cold during the long march from Hannastown.

General Washington wrote to the Pennsylvania Council of Safety on March 28: “By the promotion of Major Butler and the death of the Colo. And Lieut. Colo., the eighth Regiment of your state is left without a field officer, I must therefore desire that you will order the three new field officers to join immediately, for I can assure you, that no Regiment in the Service wants them more.”88

Colonel Daniel Brodhead later assumed command of the regiment and in 1778 it was ordered to march to Pittsburgh to resume its original function of protecting the frontier.89It took part in several campaigns, including Brodhead’s successful expedition up the Allegheny in 1779 against the Indians. On January 17, 1781, the regiment’s term of service expired and it was discharged, with some of the officers and men being assigned to other units.90

Col. Wilson’s Estate

Col. Wilson’s estate took some years to settle, with his will of September 10, 1776, not being recorded until September 25, 1790, in Fayette County. This county was formed from a portion of Westmoreland and included the site of his home. The will has been published elsewhere and copies of it can be obtained from the Register of Wills of Fayette County so I do not think it necessary to include the complete text in this work. However, a synopsis of its contents, which follows, is given so that the reader can form some impression of the extent of his estate:91

- 19 Separate tracts of land in Pennsylvania and Virginia

- 6 Horses

- 4 Slaves

- 1 Unborn Negro child

- 3 Beds

- 2 Saddles

- 1 Bridle

- 1 Rifle

- 1 Small Sword

- Ferry rights across the Cheat and Monongohela Rivers

- 117 Pounds cash to be distributed for various purposes.

The above items were enumerated from specific bequests to Col. Wilson’s wife, children and others. Reference was also made to other real and personal property to be divided equally among the children. Unless the estate was encumbered by debt, it certainly could be considered substantial in its day, even when one remembers that land in eighteenth century America was plentiful and extremely cheap by today’s standards. A complete inventory might be available from Fayette County but it really is not essential to devote much time and effort to determining the exact size of an estate so old.

Who Was Col. George Wilson, the Man?

“...basic to his personality...was pragmatism to the point of extremity”Far more important than his temporal estate, the records that still exist permit us to draw some conclusions about George Wilson the man — his character, personality and beliefs. From his letters and what we know of what others thought of him, it is easy to see that he was not lacking in intelligence and judgment, although it is equally easy to see that he had very little if any formal education. Unfortunately, no likeness or physical description of him exists, so we cannot even guess as to his appearance.

The story of his life in Augusta, Hampshire and the Monongohela Valley reveals that the outstanding traits of his character were physical courage and loyalty to his convictions. These were common among the Scotch-Irish and were the products of their Presbyterian faith and the years of turmoil and danger that they and their ancestors had experienced in Scotland and Ireland. The fact that Colonel Wilson managed to acquire substantial holdings for his time and place and that he was astute enough to pick the winner in the Pennsylvania-Virginia boundary dispute is some testimony to his canniness, another legendary characteristic of the Scotch. Another tendency he shared with his fellow Scotch-Irishmen was a certain restlessness and dissatisfaction with things as they were, which makes it somewhat easier for us to understand why he moved so frequently in a day when transportation was so primitive.92

So, it would seem we have an ancestor who is brave, loyal and astute. We also know he exhibited an aggressiveness and, when he had determined his course of action, a certain insensitivity to the consequences upon the fortunes and feelings of others. For example, his statement to St. Clair that “Wars of any cind are not agreeable...But more Especially intestin Broyls” might well have been sincere; but this didn’t seem to stop him from engaging in bitter wars with the Indians and British, brawling with the Virginians or kidnapping Dr. Connolly. This is not meant to be an accusation of hypocrisy against an ancestor who has been in his grave more than two hundred years, but it might serve as the basis for understanding why the Virginia settlers hated him so vehemently. Better yet, the reader should simply view it as an observation that all of us are finite and imperfect and have our weaknesses as well as our strengths.

So, it would seem we have an ancestor who is brave, loyal and astute. We also know he exhibited an aggressiveness and, when he had determined his course of action, a certain insensitivity to the consequences upon the fortunes and feelings of others. For example, his statement to St. Clair that “Wars of any cind are not agreeable...But more Especially intestin Broyls” might well have been sincere; but this didn’t seem to stop him from engaging in bitter wars with the Indians and British, brawling with the Virginians or kidnapping Dr. Connolly. This is not meant to be an accusation of hypocrisy against an ancestor who has been in his grave more than two hundred years, but it might serve as the basis for understanding why the Virginia settlers hated him so vehemently. Better yet, the reader should simply view it as an observation that all of us are finite and imperfect and have our weaknesses as well as our strengths.

“He was probably as quick to forgive and forget as he was to quarrel” From what we have learned of Colonel Wilson’s character, we can describe his personality with some claim of accuracy. Obviously, he was opinionated and contentious, but not to the point of severing past friendships or carrying matters beyond the possibility of compromise if he could avoid it. His letters also show quite clearly that he was outspoken and blunt, even tactless on occasion. This, to be sure, did nothing to endear him to his adversaries. Something else that was basic to his personality, as it was to practically all the Scotch-Irish, was pragmatism to the point of extremity.93 If something was not deemed valuable in an immediate and practical sense, it was not worth consideration; perhaps this is why the Scotch-Irish produced so many noteworthy politicians, jurists, educators, farmers and businessmen but not many artists, musicians or poets.94 Some have gone so far as to say that they were entirely devoid of any sense of esthetic beauty.95 George Wilson, for example, was practically illiterate if his letters are compared to those of men with whom he associated and corresponded, such as Arthur St. Clair, James Wilson, Aneas McKay, John Connolly, William Crawford and others. One might think that in his position as magistrate and a man of influence he might have made some effort to improve his spelling and syntax, yet it is painfully obvious from looking at his letters of 1771 and 1776 that he did not. Apparently, he learned enough English to read the Scriptures and express whatever thoughts he wished to his fellows and that was enough for him. Unfortunately, so many Scotch-Irishmen thought the same way that there was no contemporary history of their settlements written and scholars have had to depend on court records, letters, personal diaries and the like.96

Despite the foregoing, it would be most unfair to picture our ancestor as a boorish, insensitive lout. He was probably as quick to forgive and forget as he was to quarrel and his letters, particularly those to James Wilson and Luke Collins, show that he was not without warmth or compassion for others. We have to constantly bear in mind that he and his ancestors, through circumstances beyond their control, had lives of hardship and privation that simply did not permit the luxury of certain “civilities.”

A Man of Faith and Strong Conviction

Colonel Wilson’s beliefs are easier to catalog than his character or personality traits because they flow so logically from them, or vice versa, and are more a matter of record. He was a Presbyterian by faith and a trustee of Mount Moriah Church together with John Swearingen.97One of the early Presbyterian ministers, Rev. John McMillan, visited the Monongahela Valley in 1775, stayed at Colonel Wilson’s home and preached at Mount Moriah.98 This study is not intended to be a theological discourse and the writer is not qualified to discuss the Presbyterian faith in any detail other than to say that it was most certainly the center of the lives of the Scotch-Irish settlers in pre-Revolutionary America.

Colonel Wilson’s beliefs are easier to catalog than his character or personality traits because they flow so logically from them, or vice versa, and are more a matter of record. He was a Presbyterian by faith and a trustee of Mount Moriah Church together with John Swearingen.97One of the early Presbyterian ministers, Rev. John McMillan, visited the Monongahela Valley in 1775, stayed at Colonel Wilson’s home and preached at Mount Moriah.98 This study is not intended to be a theological discourse and the writer is not qualified to discuss the Presbyterian faith in any detail other than to say that it was most certainly the center of the lives of the Scotch-Irish settlers in pre-Revolutionary America.

In addition to his religion, Colonel Wilson obviously was a believer in law and order, possibly because his ancestors had had so little of it in their own lives.99 A strong devotion to the benefits of hard work and self-reliance was prominent in the in the Scotch-Irish settlements and did as much as any of their beliefs to shape the future of America. Such beliefs, however, were not unique to the Scotch-Irish but were shared by many of the immigrant groups who settled in this country and, at least until recently, by most twentieth century Americans.

As an individual, George Wilson did not have a significant effect on the course of American history and our country would most likely not be different today had he lived another 20 or 30 years. We recognize our debt to men like George Wilson because he and his contemporaries endured incredible hardships and dangers in taming the frontier, establishing the institutions of civilization and, most important, winning our independence. We can only hope that our descendants some two hundred years hence will think as well of us.

NOTES

1 Adams, Mrs. Marcellin G., “Colonel George Wilson: A Genealogical Study in Western Pennsylvania”, The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, Vol. 26, No's. 3 & 4, Sept.-Dec., 1943, p. 96.

2 Leyburn, James G., The Scotch Irish – A Social History, p. 89.

3 Ibid, pp. 327 ff.

4 Dickson, R.J., Ulster Emigration to Colonial America 1718-1775, pp. 19-21; 49-51; 60.

5 Adams, op. cit., p.108.

6 Dickson, op. cit., p. 221,

Leyburn, op. cit., p. 236.

Bolton, Charles K., Scotch-Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America, p. 266.

7 Dickson, op. cit. p. 226.

Dunaway, Wayland F., The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania, p. 47.

8 Leyburn, op. cit., p. 198.

Dunaway, op. cit., p. 59.

9 Ford, op. cit., p. 379.

Dunaway, op. cit., pp. 103-106.

10 Waddell, Joseph A., Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, p. 36.

11 Kegley, F.B., Kegley’s Virginia Frontier, p. 41.

12 Chalkley, Lyman, Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia, II, p. 275.

Crozier, W.A., Early Virginia Marriages, p. 85.

13 Wilson, Cora Scott, MS, The Wilson Genealogy and Allied Families, p. 33.

Chalkley, op. cit., III, p. 352.

Ibid, I, p. 147.

Ibid, I p. 371.

14 Augusta County, Virginia, Deed Book 4, page 84.

15 Augusta County, Virginia, Deed Book 7, page 516

16 Augusta County, Virginia, Deed Book 8, page 37.

17 Dunaway, op. cit., p. 145.

18 Chalkley, op. cit., I, p. 68.

19 Ibid. p. 73.

20 Adams, op. cit., p. 97.

21 Chalkely, op. cit., I, p. 317.

22 Ibid., p. 93.

23 Ibid.., p. 500.

24 Kegley, op. cit., p. 296.

25 Chalkley, op. cit., I pp. 119, 123.

26 Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1761-1765, Edited by John Pendleton Kennedy, p. 248.

27 Williams, Manning, “Romney’s Oldest House,” Romney, West Virginia Bi-Centennial Magazine.

28 Fayette County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, Sept. 25, 1790.

29 Williams, op. cit.

30 Fayette County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, Sept. 25, 1790.

31 Williams, op. cit.

32 Kegley, op. cit., p. 296.

33 Wilson, op. cit., p. 6.

34 Adams, op. cit., p. 98.

35 Ibid., p. 98.

36 Abernathey, Thomas P., Western Lands and the American Revolution, p. 91.

37 Chalkley, op. cit., I, pp. 119, 123.

38 Crumrine, Boyd, The Boundary Controversy Between Pennsylvania and Virginia, pp. 511-512.

39 Ibid., p. 514.

40 Alden, John R., A History of the American Revolution, p. 120.

41 Dunaway, op. cit., pp. 72-74.

42 Crumrine, op. cit., p. 513.

Abernathey, op. cit., p. 79.

Dunaway, op. cit., p. 73.

43 Dunaway, op. cit., p. 72

44 Ibid., p. 75.

45 Crumrine, op. cit., p. 515.

46 Adams, op. cit., pp. 98-99.

47 Pennsylvania Archives, First Series, IV, pp. 427-427.

48 The St. Clair Papers, arranged and annotated by William Harry Smith, pp. 3, 7, 9, 15 ff., 135.

49 Adams, op. cit., p. 100.

Wilson, op. cit., I, p. 31.

50 Fayette County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, September 25, 1790.

51 Chalkely, op. cit., I p. 371.

52 Waddell, op. cit., p. 370.

53 Wilson, op. cit., p. 31.

54 Pennsylvania Archives, Fifth Series, IV, p. 577

55 Pennsylvania Archives, First Series, IV, pp. 454-455.

56 Crumrine, op. cit., p. 522.

57 Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Records, X, p. 77.

58 Ibid., p. 78.

59 Ibid., p. 78.

60 Pennsylvania Archives, First Series, IV, pp. 466-467.

61 Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Records, X. pp. 141-142.

62 Ibid., p. 167.

63 Ibid., p. 165-166.

64 Ibid., p. 167.

65 The St. Clair Papers, I, pp. 294, 295n., 296.

66 Alden, op. cit., p. 120.

67 Adams, op. cit., p. 100.

68 Crumrine, op. cit., pp. 515-516.

69 The St. Clair Papers, I, p. 351n.

70 The Washington-Crawford Letters, cf. The St. Clair Papers, I, p. 356.

71 The St. Clair Papers, I, p. 358.

72 Ibid., I, pp. 363-365.

73 Peyton, Lewis, History of Augusta County, Virginia.

74 American Archives, Fifth Series, II, p. 7.

Ibid., I, p. 1586.

75 The St. Clair Papers, I, pp. 379-379.

76 Ibid., pp. 641-642.

77 Adams, op. cit., p. 96.

78 Smith, Charles Page, James Wilson, p. 8.

79 Ibid., pp. 68-70.

80 The St. Clair Papers, I, pp. 379-381.

81 Ibid., p. 382.

82 Stryker, William S., The Battles of Trenton and Princeton.

83 Ibid.

84 Wilson, op. cit., p. 61.

85 Pickering, Octavius, The Life of Timothy Pickering, I, p. 122.

86 Adams, op. cit., p. 101-102.

87 American State Papers, Claims, p. 276.

88 Writings of Washington, VII, p. 326.

89 Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, X, p. 645.

90 Ibid., p. 648.

Alden, op. cit., p. 434.

91 Fayette County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills, Sept. 25, 1790.

92 Leyburn, op. cit., pp. 199-200.

93 Ibid., 324-325.

94 Ibid.

95 Ibid.

96 Waddell, op. cit., pp. 45-46.

97 Adams, op. cit., p. 100.

98 Veech, James, The Monongahela of Old, p. 100.

99 Leyburn, op. cit., p. 257.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources

American Archives, Published by M. St. Clair and Peter Force, Washington, 1848.

American State Papers, Washington, 1834.

Augusta County, Virginia, Index to Deeds.

Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia, extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County, 1745-1800, compiled and edited by Lyman Chalkley, 3 vol's., Rosslyn, Va., 1912.

Fayette County, Pennsylvania, Register of Wills.

Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1761-1765. Edited by John Pendleton Kennedy. Richmond, Va., 1908.

Pennsylvania Archives, 9 series, Philadelphia and Harrisburg, 1852-1931.

Pickering, Octavius, The Life of Timothy Pickering. 4 vol's.

The St. Clair Papers. Arranged and Annotated by William Henry Smith. 2 vol's., Cincinnati, 1882.

Virginia Soldiers of 1776. Compiled from Documents on File in the Virginia Land Office by Louis A. Burgess. Richmond, Va., 1927.

The Writings of George Washington. From the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799. Edited by John C. Fitzpatrick. 39 vol's. Washington, 1932.

Secondary Sources

Abernathy, Thomas P., Western Lands and the American Revolution. New York, 1959.

Alden, John R., A History of the American Revolution. New York, 1969.

Bolton, Charles K., Scotch-Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America. Boston, 1910.

Crumrine, Boyd, The Boundary Controversy Between Pennsylvania and Virginia. Pittsburgh, 1892.

Dickson, R. J., Ulster Migration to Colonial America 1718-1775. London, 1971.

Dunaway, Wayland F., The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania. Chapel Hill, 1944.

Ford, Henry Jones, The Scotch-Irish in America. Princeton, 1915.

Hanna, Charles A., The Scotch-Irish. 2 vol's. New York, 1902.

Heitman, Francis B., Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army. Washington, 1914.

Kegley, F. B., Kegley’s Virginia Frontier. Roanoke, 1938.

Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish, A Social History. Chapel Hill, 1962.

Peyton, Lewis, History of Augusta County, Virginia. Bridgewater, Virginia, 1953.

Smith, Charles Page, James Wilson. Chapel Hill, 1956.

Stryker, William S., The Battles of Trenton and Princeton. Cambridge, 1898.

Veech, James, The Monongahela of Old. Pittsburgh, 1892.

Waddell, Joseph A., Annals of Augusta County, Virginia from 1726 to 1871. Staunton, Virginia, 1902.

Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. Pittsburgh, 1916 –

Wilson, Cora Scott MS, The Wilson Genealogy and Allied Families, Milwaukee, 1958.

Edited for World Wide Web by Mary Wilson Reynolds, 2008

Please direct inquiries to: Fine Art by Mary